“The myth of the good tsar” is prominent in Russian history, both in the imperial period and in the modern one. Sometimes, as with the case above, people can bring about change, as Tsar Alexei implemented reforms based on the petition the next year. However, in the 1930s when Communist Party members dragged off to GULag (the Soviet prison / labor camp system) wrote to Joseph Stalin telling him what happened and asking him to fix what his evil advisors had done, nothing changed – in this case because it was Stalin who was behind the Great Purges himself. Though in this case, it is also worth noting that Stalin helped brand the Purges as the “Ezhovschina” blaming them on the head of the security services, Ezhov – feeding into the idea that it was evil advisors not himself who was responsible.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, head of Wagner

The parallel to what has been happening this week in Russia is clear. Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner Group, has been feuding with the Russian military and particular the Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, accusing them of incompetence in the Ukraine war. Vladimir Putin has tried to stay out of this war of words, and even invited the two to a sit down at the Kremlin earlier this year to attempt to make peace, though to no avail. Last week things came to a head when someone in the Russian military allowed for an attack on Wagner forces. Whether this was the defense minister himself or a subordinate general, or was itself a false flag operation, is not known publicly. It is also not known if that person felt that they had Putin’s permission to do this. One is reminded of Henry II’s “will no one rid me of this troublesome priest” leading to three of his knights killing Archbishop Thomas Becket and creating a martyr and saint.

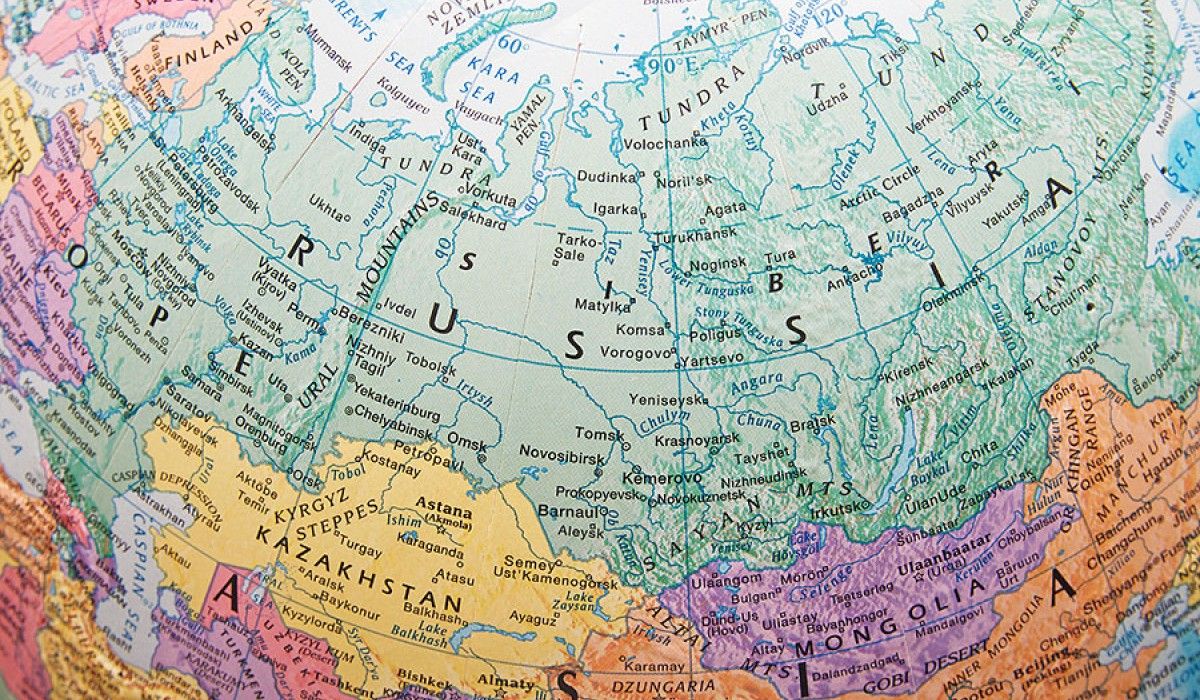

For Prigozhin, the Russian military attack on Wagner was the last straw, and he seized the Rostov military facilities. Not only did he do this bloodlessly, and with planning beforehand, but it might also indicate collusion with some members of the Russian military. After solidifying Rostov, Prigozhin’s forces launched what he called a “march for justice” moving up the M4 motorway directly toward Moscow. Prigozhin’s label for this is telling; he never once demanded that Putin surrender or resign, and he did not claim to be a savior of Russia. He was very clear that his enemies were the incompetent commanders of the Russian military who had been leading a disastrous war effort in Ukraine and who had purposefully hamstrung, and then attacked, Wagner. In other words, his target was the tsar’s evil advisors.

Lukashenko and Putin

The intervention by the Belarusian leader, Alexander Lukashenko, was a surprising way to end the incident, but it allowed Putin to keep his hands clean of the whole affair and not be directly involved in talks with Prigozhin. The public does not know what was talked about, nor agreed upon, apart from an amnesty for Wagner troops and Prigozhin himself going to Belarus. The fact that Belarus is largely a satellite of Russia now makes that little safer for Prigozhin, so one can suggest that something else was agreed upon which might provide for his safety. One possibility was that his concerns would be heard, and that Shoigu would be removed. This seems to have been contradicted by a video released by the Kremlin on Monday (June 26) showing Shoigu purportedly meeting with troops on the Ukrainian front. Thus, what the full quid pro quo was only time will tell.

As for future ramifications, the same is true. Putin is a strongman, and thus he needs to project strength to rule. If there is a hint that this makes him look weak, and there is more than a hint, he will need to do something to react and look strong. A new attack on Ukraine could be just that, though the Russian military is stretched thin already with the Ukrainian offensive. The political absorption of Belarus could be another way to demonstrate his strength and claim a victory, though this is unlikely after Lukashenko’s role in deescalating Prigozhin. Some commentators have worried that the show of strength might be an increased threat of nuclear weapons. I find this unlikely as using nuclear weapons is a step that would cement condemnation from groups that have held back, thus far, from publicly judging the Russian invasion of Ukraine. So, once again, we will have to wait and see.

A famous quote, variously attributed, is that “one must learn from history in order to avoid repeating it.” It is worth noting that history is not a playbook for the future. Similar things can happen, and knowing history gives one context for understanding events and people, but it does not provide all of the answers (I am sorry to say). Thus, we must stay tuned.

- By Christian Raffensperger, Professor of History and Wray Chair in the Humanities

Earning his B.A. from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine, and his M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, Raffensperger is active in several scholarly organizations. He recently served on the governing board of the Byzantine Studies Association of North America and the board for the Ohio Academy of History. Additionally, he is also a founding member of the editorial board for the journal, The Medieval Globe. The National Humanities Center in Durham, North Carolina, awarded Raffensperger with his most recent fellowship, the Archie K. Davis Fellowship.